Ireland

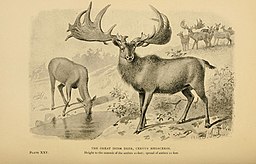

The European country of Ireland was first settled around 6000 BC by a race of Middle Stone Age hunter-gatherers who lived there. They tended to hunt such creatures as the megaceros, a giant variety of deer so large that their antlers spanned ten feet. Around 3000 BC, they made significant technological improvements that moved them into the classification of Bronze Age people.[1] These people eventually came to be known as the Picts, who ruled over Ireland for millennia and even expanded to Scotland.

The Celts

Around 900 BC, a new race known as the Celts appeared. They were the result of cross-breeding between European Bronze Age people and wanderers from central Asia.[3] They dominated the country for many years to follow, building many of the characteristic ring forts, over 40,000, which are found all over Ireland. However, they did not confine themselves to just Ireland, dominating Western Europe for a long time, sacking Rome in 390 BC, and Delphi a century later.

Celts were often identified by their specific culture and by their use of the Celtic languages.[5] The exact timing of how and when the Celts came into Ireland is still a controversial topic between historians today and there are many different theories regarding the exact history of the race.[6]

One theory claims that Celtic culture was first found during the Bronze Age Urnfield culture (1300 BC - 750 BC); however, another theory proposes that the Celts weren't seen until the start of the Iron Age Hallstatt culture (1200 BC - 500 BC).[7] By the time of the Iron Age La Tène period, which began around 450 BC and ended with the Norman Conquest in 1st century BC, Celtic culture had expanded all over Europe, as far east as modern-day Turkey.[5]

The Roman Empire expanded massively throughout the 1st millennium, therefore Celtic culture and languages became limited to Ireland, Wales, Scotland, Cornwall, the Isle of Man, and Brittany (French: Bretagne). Between the 5th and 8th centuries, Celtic culture was booming and became a strong entity, but by the 6th century Celtic languages began to fall out of use.[8]

St. Patrick

St. Patrick, the patron saint of Ireland, was a Romano-British missionary in Ireland during the 5th century.

In the early 5th century AD, St. Patrick came to Ireland to convert the Irish, who were all Druidic, to Christianity, which is why he is now regarded as the founder of Christianity in Ireland. Interestingly nearly everyone living in Ireland today is Christian and Druids are almost unheard of. This feat was made even more impressive by the fact that the Celtic nobility held their power through the Druidic religion; because of this, they were exceptionally difficult to convert.

The years that were the Dark Ages for the rest of Europe, between 410 and 800 AD, were a golden age for Ireland. Ireland flourished while the Roman Empire fell and was plagued by attacks from Vikings, Muslims, and Magyars. Unfortunately, this didn't last and Ireland would eventually have its own Dark Age beginning around the year 100 BC and ending in AD 300.

In 795, Vikings from Scandinavia landed on the Gaelic island of Iona and plundered a monastery there. By the early 800's, they had begun raids on Ireland itself, plundering it on a regular basis. At first, they were only interested in rape, pillage, and plunder, but something changed their desire of looting then leaving as eventually, they stayed. By 841, they had established several well-fortified settlements in Louth and expanded aggressively thereafter, eventually conquering all of Ireland with a decisive victory in the Battle of Dublin in 919. The Celts slowly regained land however, and in 1014, led by Brian Boru, they almost completely eliminated the Viking presence in Ireland with the Battle of Clontarf.

March 17th is believed to be the day that Patrick died. This day remains his Feast Day and is celebrated annually in countries all over the world as St. Patrick's Day.

Norman Invasion of Ireland

Next came the Normans, who were originally of Viking origin. While some Vikings were raiding Ireland in the previous centuries, the Normans had settled in northern France and were intermarrying with the natives. From there, they swept through England and Scotland and eventually came to Ireland in 1169.

Robert FitzStephen and Maurice de Pendergast, along with 460 armed men, arrived at Bonnow Bay, County Wexford on May 1, 1169, and joined together with 500 men led by Diarmait Mac Murchada, King of Leinster.[10] Within a few years, they had captured Dublin and most other major cities, thus Ireland belonged to them. They intermarried with the Celts, who now called themselves the Gaels, giving rise to many powerful Norman-Irish feudal families.

Then, a feud which was to change the fate of Ireland began between two powerful families: Tiernan O'Rourke and Dermot MacMurrough. Two other families joined in as well; Rory O'Connor sided with O'Rourke and Murtogh MacLochlain protected MacMurrough. In 1166, O'Rourke and O'Connor triumphed and chased MacMurrough out of Ireland.

Strongbow

MacMurrough was not to be discouraged however; he returned shortly thereafter with an army provided by Henry II and the assistance of the legendary Richard FitzGilbert de Clare, also known as Strongbow. He eventually managed to take over Ireland and instated himself as the ruler there. He became sick and died after a short reign, and left his throne to Strongbow. O'Connor and O'Rourke raised an army and attempted to instate MacMurrough's nephew, with whom they sympathized, instead of Strongbow but they were defeated.

Strongbow, therefore, became King of Ireland, but King Henry had plans of his own. He had provided the army that conquered Ireland, and he wanted Ireland in his empire. So he brought a new army to Ireland, consisting of over 4000 troops. Strongbow surrendered Ireland to him without a drop of blood being shed.

For a long time thereafter, Ireland was divided between the Normans and the Gaels. Though the Normans controlled most of the Island, there was eventually a Gaelic resurgence and the Norman territories were vastly reduced. Once this happened, the Normans began to be assimilated and eventually became "more Irish than the Irish."

Though still affiliated with England, Ireland was essentially independent. The Tudor Dynasty (1485-1607) put an end to this, engaging in another conquest of Ireland and instating laws which, among other things, decreed that the King of England was automatically the King of Ireland, essentially making the two a single country. They also ousted the Catholic church, making Protestantism the religion of Ireland and also imposed laws which created a huge class distinction, setting the stage for the bloody conflicts that rage to this day.

Plantation of Ulster

Ulster was originally the most independent and Gaelic territory of Ireland.[12] Ulster was extremely rural and the main focus of its inhabitants was agriculture, specifically cattle farming.[13] At the end of the Nine Year's War (1594 - 1603), the Plantation of Ulster was first proposed. It was first proposed to James VI & I, King of Scotland and King of England and Ireland after the union of the crowns in 1603, as a way to "civilize" the territory of Ulster.[14]

The so called Plantation of Ulster occurred during the reign of King James I. Six entire counties, Armagh, Tyrone, Coleraine, Donegal, Fermanagh, and Caven, of Ireland were 'planted' with English and Scottish settlers.[15] The settlers were Protestants and were sent by the English crown to make the territory easier to rule. More than 8,000 people of British birth were found in these counties by 1620.[14]

The Plantation of Ulster was to have a profound impact on Ireland and it's relationship with the United Kingdom for centuries to come.

Potato Famine and Exodus to the Colonies

From 1740 onwards, the population of Ireland began to soar. For the next eighty years, the largely agricultural economy of Ireland enjoyed a period of prosperity due to increased production and high British grain demands. However, by the 1830's, the once-fertile soil had grown depleted from heavy overproduction, and agricultural productivity fell off.

The middle of the 1840's marked the onset of catastrophe for the Irish potato crop. A partial failure of the vital staple crop in 1845 was followed by a complete failure the following year, which was in turn followed by an especially cruel winter. In 1848, the crop failed once again. Starvation and disease became common as many farmers were driven penniless from their homes. The Irish Potato Famine resulted in one of the most dramatic waves of migration in history.

From 1845 to 1851, Ireland lost almost a quarter of its population. Of these, half emigrated to Britain, North America, and Australia. The other half perished. Most Irish immigrants were virtually penniless and were often perceived to be lower-class and less hard-working, but nothing could be further from the truth. Time would prove their critics very wrong.

See Also

- Ancient Origins of Ireland

- The O Prefix

- The Mac and Mc Myth

- Irish Septs

- Strongbow

- Plantation of Ulster

- Cromwell's Invasion of Ireland

- Undertakers

- The Provinces of Ireland

- Wild Geese

- Irish Potato Famine

References

- ^ Gould, S.J. "The misnamed, mistreated, and misunderstood Irish elk", Ever Since Darwin. W.W. Norton & Company, 1977.

- ^ "File:Cervus Megaceros.jpg." Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. 8 Jun 2018, 16:15 UTC. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Cervus_Megaceros.jpg&oldid=305250013

- ^ Reich, David. Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past. Oxford University Press, 2018.

- ^ "File:Ring Fort near Cahirsiveen - panoramio - Adrian Farwell.jpg." Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. 31 Oct 2019, 20:47 UTC. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Ring_Fort_near_Cahirsiveen_-_panoramio_-_Adrian_Farwell.jpg&oldid=372734736

- ^ Koch, John. Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. 2005.

- ^ James, Simon. The Atlantic Celts – Ancient People Or Modern Invention. University of Wisconsin Press, 1999.

- ^ Chadwick, Nora. The Celts. Penguin Books, 1970.

- ^ Cunliffe, Barry. The Celts – a very short introduction. Oxford University Press, 2003.

- ^ "File:Saint Patrick Catholic Church (Junction City, Ohio) - stained glass, Saint Patrick - detail.jpg." Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. 2 Nov 2019, 11:01 UTC. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Saint_Patrick_Catholic_Church_(Junction_City,_Ohio)_-_stained_glass,_Saint_Patrick_-_detail.jpg&oldid=372932764

- ^ Kearney, Hugh. The British Isles: A History of Four Nations. Cambridge University Press, 2012.

- ^ "File:Strongbow.jpg." Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. 10 Jun 2019, 15:48 UTC. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Strongbow.jpg&oldid=353842776

- ^ Madden, R.R., The United Irishmen, Their Lives and Times Volume 1. J. Madden & Co., 1845.

- ^ Bardon, Jonathan. The Plantation of Ulster. Gill & Macmillan, 2011.

- ^ Canny, Nicholas. Making Ireland British, 1580 - 1650. Oxford University Press, 2003.

- ^ Stewart, A.T.Q., The Narrow Ground: The Roots of Conflict in Ulster. Faber & Faber Ltd., 1989.

- ^ "File:Portrait of King James I & VI.jpg." Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. 19 Nov 2016, 03:23 UTC.https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Portrait_of_King_James_I_%26_VI.jpg&oldid=215551892

- ^ "File:Memorial to the Irish Potato Famine, St Lukes, Liverpool (2).JPG." Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. 3 Feb 2018, 22:57 UTC. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Memorial_to_the_Irish_Potato_Famine,_St_Lukes,_Liverpool_(2).JPG&oldid=285133879

- ^ Martin, Francis Xavier. A New History of Ireland, Volume II: Medieval Ireland 1169-1534. Oxford University Press, 2008.

- ^ Swyrich, Archive materials