Scotland

The long history of the lands of the northern third of Great Britain has been violent and often tragic. The castles and ruins, the songs and the legends tell Scotland's tale. It is the harshness of its history and the ruggedness of its land that have shaped its proud inhabitants. How the country came to be, and evolved, has long taxed the minds of many historians.

|

Contents

|

Archeological records show that the first nomadic hunters and gatherers came to the area over 6,000 years ago, as the last remains of the ice age crept northward. The first recorded history of Scotland was by the Roman historian Tacitus in the first Century A.D., who called the people the Picts, and referred to them as "savages", and "fierce enemies". It was in order to fight the Romans that the warring clans began to unite. The Romans had conquered all the rest of Britain, but were never able to subdue the Caledonian clansmen of the north, and in the end constructed Hadrian's Wall, an imposing stone barrier stretching from sea to sea, to protect them from the marauding Picts.

Alban (Alba) was born

Shortly after 400 A.D., the Romans left the British Isles, and Scotland began to emerge from the dark ages. There were four peoples inhabiting what was then called Alban: the Picts, the Scots, the Britons, and the Angles, when invasions by Vikings began. By 843, Kenneth MacAlpin, King of the Scots of Dalriada held all lands north of the river Forth, and renamed the kingdom: Scotia. Duncan I (portrayed in Shakespeare's Macbeth) added to this kingdom the rest of mainland Scotland. Although there followed a period of peace with England, war between Scotland and Norway was constant, as was infighting in Scotland itself.

English Reprisals

King Edward I of England fought off a Scottish invasion by John Balliol, and then rampaged through Scotland, eventually capturing the Stone of Scone, the ancient stone of destiny upon which Scottish kings had been crowned for seven centuries. He placed the stone in Westminster Abbey, where it stayed until it was stolen back by Scottish nationalists in 1950. The stone was formally returned to Scotland on November 15, 1996, and is now on display in Edinburgh Castle. For his exploits, Edward I earned the nickname "Hammer of the Scots".

The Scots continued attempts to free themselves of England's tyranny. One of Scotland's greatest national heroes, Robert the Bruce, had himself crowned at Scone in 1306. His uprising was defeated, but Bruce was not killed. He became a famed outlaw who harassed the English armies using guerilla tactics, and uniting Scottish noblemen to his cause. By 1314, Bruce had driven the English out of every town in Scotland, save Stirling.

In 1371, Robert Stewart became the Scottish king, the first in a long line of Stewarts (later spelled "Stuart"). There had been several child kings and much strife when James IV came to the throne at age fifteen. He managed to control lowland rebellions, and attempted to make peace with the Highland Clan chiefs. In 1502, James IV signed a treaty of perpetual peace with England, and married Margaret Tudor, daughter of King Henry VII of England, thus paving the way for the eventual union of the crowns.

The Stuart line was to come to an end with Mary Queen of Scots, one of history's most prominent women. Mary became Queen of Scotland when she was just a week old. Henry the VIII arranged for Mary to marry his young son, and so when Mary's mother rejected this treaty of marriage, Henry responded with a vengeful onslaught, burning and pillaging in Edinburgh and the Border Country. Mary returned from France at age eighteen, widowed, beautiful, strong-willed, and Catholic. Her attempt to rule a Scotland that had renounced the Catholic Church in favor of Protestantism in 1557 was plagued with difficulties. Eventually, Mary was forced to abdicate in favor of her one-year-old son James VI. She fled to England, to her cousin Queen Elizabeth I. Due to her claims to the English throne, Mary was imprisoned in the Tower of London, and then beheaded in 1587. The two queens never met, and some historians suggest that Elizabeth was insanely jealous of Mary's beauty and charm.

In 1583, James VI escaped from his Protestant kidnappers, and resumed the throne of Scotland. When Elizabeth I died in 1603, James was her only heir; thus he became James I of England, as well as James VI of Scotland. James' most lasting legacy is the King James Bible; the translation of the bible into English still favored by many Protestants. The union of the crowns did not however put an end to struggles in Scotland.

Civil war in England in 1642 pitted the cavaliers fighting for King Charles I against the Roundheads of Oliver Cromwell's parliament. When the victorious Cromwell forced the execution of Charles I, the Scottish proclaimed Charles' son as their king. Cromwell, incensed, invaded Scotland, uniting the two countries under a strong, central, civil government. Upon Cromwell's death, the English Monarchy was restored to the throne. Many Scots felt they had lost their independence, and the stage was set for uprisings.

The Jacobites

The Jacobites wanted the return to a Stuart king for Scotland, and periodically took up arms to this end. By 1707, the English line of succession had passed to the Queen Sophia of the German Hannover family. The Scots agreed to a union of parliaments and a Hannoverian succession in return for commercial equality, use of their own legal system and the Presbyterian religion. The Jacobite rebellion grew, as did opposition to the union of the parliaments. In 1715, James Edward rallied the Scottish clans around him, and was proclaimed king of Scotland. However, the great families of Scotland were not united, and the uprising was defeated.

Despite attempts by the English to disarm the clansmen and ship Jacobites to plantations in America, the Jacobites rose again. Bonnie Prince Charlie, a handsome and charming man, gradually drew support until he led 3,000 clansmen to Edinburgh to reinstate his father, James Edward, as king of Scotland. After winning several battles in Scotland, Charles crossed the border and pushed southward toward London. Only a few hundred kilometers from London, a fatal decision was made to withdraw to the highlands in order to raise more troops. Scotland was as divided as ever, many clans supporting the Honoverian side, and a large, well-equipped army was facing Charles. Finally, on Culloden Moor in 1746, Charles' ragged and hungry Highlanders were slaughtered by the English cavalry. Charles, however, escaped by rowboat to the Isle of Skye, disguised as a maidservant. And, even though the English put a price on his head of 30,000 pounds (an incredibly large sum of money for the time), no one ever betrayed him.

The English response to these uprisings was vengeful and cruel: whole villages were burned and clansmen were slaughtered or shipped to the plantations. In fact, the English tried to destroy the clan system with the Disarming Act of 1746: no Scot was allowed to bear arms, and the wearing of Clan tartans and even the playing of bagpipes were banned. The penalty for wearing 'any part whatsoever' of the Highland dress was six months in jail for a first offense.

Miraculously, many of the Scottish traditions survived and have flourished, making the Clan tartan one of the most powerful worldwide symbols of kinship. Gradually, the restrictions were dropped, and Scotland as part of Great Britain entered a period of peace and prosperity that continues to the present day.

See Also

- King Edward I

- The Border Clans

- Strathclyde Britons

- Boernicians

- Vikings

- Picts

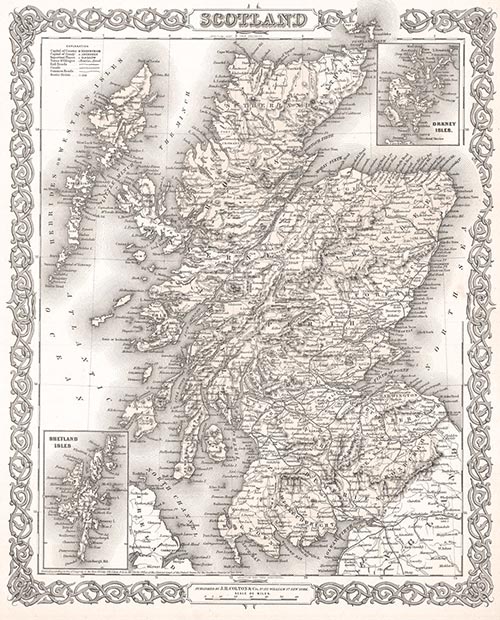

- Regions of Scotland

- Scottish Clans

- Scottish Septs

- Mc and Mac

References

- ^ Swyrich, Archive materials