Anglo-Saxons

The Anglo-Saxon period typically refers to the time in Britain from the year 450 up until the Norman Conquest in 1066.[1] The Anglo-Saxons were a cultural group formed by Germanic people that moved from mainland Europe to Britain. The Anglo-Saxons are responsible for the majority of the modern English language as well as the legal system and general society in England today. The language that was used at that time by the Anglo-Saxons is typically referred to as Old English in modern research.[2]

In the 5th century, Great Britain had recently been deserted by the Roman legions which led the Anglo-Saxons to establish the independent kingdoms of Northumbria, Mercia, Wessex, Kent, Essex, Sussex, and East Anglia, which were collectively known as the Heptarchy.[3]

The time from 410 to 560 is now commonly known as the Migration Period, or the Völkerwanderung in German.[3] The most common migrants were the Germanic tribes of Goths, Vandals, Angles, Saxons, Lombards, Suebi, Frisii, and Franks.[4] A small area of land in the south-eastern part of England and a supply of food was given to the Saxons in exchange for them protecting Britain from potential danger caused by the Picts and Scoti. The exact number of migrants at this time is not known; however, archeologists have speculated anywhere from 20,000 to 100,000, and by the year 500 the Anglo-Saxons were established in the southern and eastern parts of Great Britain.[5]

In the late 6th century the Anglo-Saxon society began to develop more rapidly. According to researchers, four main things contributed to this: more freedom for the ceorl (non-servile peasant), larger kingdoms, warriors becoming kings, and the development of monasticism under Finnian and Columba, two Irish Christian missionaries.[1]

Throughout the 6th and 7th centuries, the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms engaged in heroic battles for military supremacy and were gradually converted to Christianity. In 595, Pope Gregory the Great, also known as Saint Gregory, chose Augustine to travel to the town of Canterbury on the Isle of Thanet. Augustine led the Gregorian Mission to spread Christianity in Britain and to guide them away from Anglo-Saxon paganism. After Augustine's mission in the late 6th century, English Christianity was consolidated. [7]

In the 8th century, the Anglo-Saxons were violently attacked and devastated by the Vikings, and by the 9th century, the Vikings sporadic forays into England became a recurring harassment. Also during the 9th century, the country was divided between the four rival kingdoms of Northumbria, Mercia, East Anglia and Wessex, which were later unified by King Egbert of Wessex.[9]

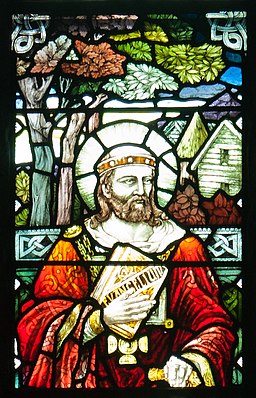

In 994, the Danes invaded England, and this invasion eventually led to the expulsion of the Anglo-Saxon King, Æthelred, also known as Æthelred the Unready. Æthelred fled to Normandy, where his family remained until 1042. The constant attacks brought extremely hard times for England and after this the Anglo-Saxon rulers never truly recovered their lost power. Æthelred earned the name Æthelred the Unready because he was unprepared for the brutal attacks from the Vikings which almost completely destroyed his country. After 1042, a Danish dynasty of kings ruled and then Edward the Confessor, son of Æthelred, ascended the throne.[10]

Upon the death of Edward in 1066, the elected king was challenged by Duke William of Normandy. William's successful invasion in 1066, known as the Norman Conquest, ushered in the reign of the Norman kings. The Norman Conquest from France and their victory at the Battle of Hastings, meant that many Anglo-Saxon landholders lost their property to Duke William and his invading nobles. By 1087, only about 8 percent of the land belonged to the Anglo-Saxons. Despite this change of leadership, English culture remained predominantly Anglo-Saxon; however, the Anglo-Saxon culture was changing.[12]

The early years of Norman rule were marked by rebellion and oppression. William sought to achieve political stability by centralizing authority upon the king, and although learning was encouraged during William's reign, many of his policies were tyrannical in nature. Under this oppressive Norman rule many families decided to move north to Yorkshire and beyond the border into Scotland.

Under the Tudors the problems of succession, strife between Catholics and Protestants, and the fear of foreign invasion had mainly been resolved. Later, under the House of Stuart, there were conflicts between the king and parliament, and between the Catholics and the Protestants. The Stuarts came to power at a time when the middle class was becoming increasingly powerful and willing to assert its rights through parliament. The Stuarts were ousted from power first by Cromwell and then by the Glorious Revolution which resulted in the long series of Jacobite uprisings.

References

- ^ Higham, Nicholas J. and Ryan, Martin J. The Anglo-Saxon World. Yale University Press, 2013.

- ^ Hogg, Richard M. The Cambridge History of the English Language: Vol 1: the Beginnings to 1066. Linguistic Society of America, 1992.

- ^ Hines, John. "Cultural Change and Social Organisation in Early Anglo-Saxon England", After Empire: Towards an Ethnology of Europe's Barbarians. Boydell & Brewer, 2003.

- ^ Bury, J. B. The Invasion of Europe by the Barbarians. Norton Library, 1967.

- ^ Brooks, Nicholas. "The Formation of the Mercian Kingdom", The Origins of Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms, 1989.

- ^ "File:Kildare Cathedral Nave South Window 05 Saint Finnian of Moville Detail 2013 09 04.jpg." Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. 28 May 2018, 06:58 UTC. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Kildare_Cathedral_Nave_South_Window_05_Saint_Finnian_of_Moville_Detail_2013_09_04.jpg&oldid=303425930

- ^ Flechner, Roy. "Pope Gregory and the British", Histoires de Bretagnes 5. The University of Western Brittany, 2015.

- ^ "File:Pope Gregory I illustration.jpg." Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. 8 Jun 2018, 12:03 UTC. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Pope_Gregory_I_illustration.jpg&oldid=305213276

- ^ Keynes, Simon. "Edward, King of the Anglo-Saxons", Edward the Elder. Routledge, 2001.

- ^ White, Stephen D. "Timothy Reuter, ed.", The New Cambridge Medieval History, 3: C. 900–c. 1024. Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- ^ "File:St Edward the Confessor - stained glass.jpg." Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. 27 May 2018, 08:15 UTC. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:St_Edward_the_Confessor_-_stained_glass.jpg&oldid=303234096

- ^ Wood, Michael. In Search of the Dark Ages. BBC Books, 2005.

- ^ "File:066-William - Duke of Normandy.png." Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. 3 Aug 2018, 18:30 UTC. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:066-William_-_Duke_of_Normandy.png&oldid=313512850

- ^ "File:Oliver Cromwell by Samuel Cooper.jpg." Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. 23 Oct 2019, 16:53 UTC. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Oliver_Cromwell_by_Samuel_Cooper.jpg&oldid=371658642

- ^ Swyrich, Archive materials